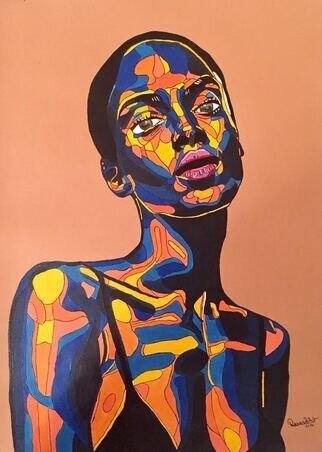

Igbo Vernacular Artist REWA

My next interview is with REWA, a self-taught painter based in Nigeria and London. REWA is known for creating Igbo Vernacular Art; paintings that explore and celebrate the Igbo culture of Nigeria. REWA's vibrant portraits depict the women of Igboland as they experience varying roles in society and shifts in power throughout their lifetime. In her work, REWA creates female-centered narratives that serve as an exploration into all aspects of Igbo culture: from rites of passage to marital ceremonies and sacred rituals. After returning to Nigeria from London, REWA dedicated herself to learning about the Onitsha people and seeks to educate others about the rich history, traditions and beliefs of the Igbo culture.

Hi Rewa! Tell me about your background and where your creative journey began.

I am a self-taught visual artist, born and raised between Nigeria and England and received a BSc. in Physiology and Pharmacology from University College London (UCL). I go between London and Lagos where I live with my husband, our perfect baby boy and our English cocker spaniel – she’s a pain in the proverbial.

Formally, my creative journey began in 2016 when I was living in Johannesburg but informally, it began much earlier than that. I’ve always had a relationship with art. Growing up, my father encouraged my creative drive and his expansive art collection from West Africa provided further impetus for my development. I’ve always doodled and sketched but it wasn’t until 2016 that I truly discovered my artistic style and began to create consistently and in earnest.

How has your art practice shifted or evolved over the last few years?

Since I began painting, I have become a lot more confident in my style and output. I started off with smaller portraits on paper using watercolour pencils. I have since graduated to figurative art using acrylic paints on ever-growing canvases. I have also become very clear on the direction of my work and the messaging I want to convey. When I began painting, I was fine with designating my paintings with the Contemporary African Art label. However, I have since chosen to label my works as Igbo Vernacular Art. The reason for this is that I believe that I have created a truly original body of work that exists outside formal academic or Western dialogue. My art is drawn from life itself and deeply anchored in a place and culture from which it was derived. This is the Igbo culture pertaining to the Igbos of Nigeria.

Your work explores the culture, history and beliefs of the Onitsha people of Igboland. What led you to study and depict this particular culture, and what do you hope viewers will take away from your work?

At risk of sounding pedestrian, my art is drawn from life itself and deeply anchored in the place and culture from which it was derived, that is, the culture of the Igbos of Nigeria. For context, the Igbos are one of the three major tribes of Nigeria and comprise the largest group of people living in south-eastern region of the country.

I spent my formative years in England, raised with my biracial mother and white grandmother. I only returned to Nigeria in 2016 and began learning about my heritage in earnest. So with my art, it was very important to me to draw on elements of cultural awareness and audience education with my work because I didn’t just want to create art for art’s sake. It is my hope that one day, my work will be included in art historical dialogue about Africa, beyond the confines of the wide-reaching Contemporary African Art designation, therefore, edification plays a huge role in my narrative.

This was very prevalent in my series, INU NWUNYE: Bride Price.

This series showcased a young woman’s passage from INYO-UNO – the knocking / introduction ceremony which heralds a betrothal, IBUNABAITE – the bride’s primary visit to her fiancé’s home, URI – eight days spent with the bridegroom’s family where she is assessed as a worthy potential housewife, through to IGO MUO and INU-MMANYA – the marriage and (palm) wine-carrying ceremony.

Many of these traditions, mainly the IBUNABAITE and URI aspects, have since died out as cultural customs faded to the pervasive western systems.

Having recently undergone both traditional and white (western) marriage ceremonies myself, I was keen to depict and highlight the now obsolete marital practices of the Igbo culture. In this way, I educate an audience and in the process, educate myself.

How a culture survives depends on its people’s capacity to learn and transmit it to succeeding generations. Post-colonialism, we imported Western practices and customs. Through my art, I would like to provide viewers with an understanding of who we are as a people, educate about our rich legacy and educate a wider audience on the symbolic practices of our forebears before it is lost entirely.

In your series, "The Pantheon," you portray female deities from the tribes of Nigeria. Can you tell me about the goddesses in this series, and what inspired you to create this collection?

I thoroughly enjoyed this series and showcasing the various female goddesses. I think it is a great pity that we glorify Thor but vilify Sango and Amadioha – his African counterparts. We all know of Aphrodite and Artemis but hardly anything is known of Yemoja, Osun or Ala / Ani. In West Africa, we have a tendency to reject and denigrate our own deities, saying they are evil and using the term ‘juju’ in a disparaging way. However, those of the west are perfectly accepted and even hallowed in popular culture and literature. I created The Pantheon as a way to change this narrative. I felt that if I portrayed our goddesses as beautiful, colourful and inviting, viewers would be more interested in learning about our own deities and they would see that there is nothing evil about them, they aren’t associated with black magic or any such folly. They are much like those of the west, just with different names. They are the gods of our ancestors and existed and worshipped long before the existence of Christ was known amongst our people

When did you join Instagram, and how has it impacted you as an artist?

In a major, major way. I joined Instagram in April 2016. Instagram has sustained my art career to a large extent. It has provided visibility to collectors, fans (I hope this doesn’t come across as arrogant!), galleries and provided me with some fantastic opportunities. ReLe Gallery and the Gallery of African Art (GAFRA) both discovered me through Instagram. I got chosen for the Nike campaign that I worked on last year, via Instragram. I am utilizing social media a lot more than I previously did, fostering new relationships electronically, discovering new artists and exciting collections as some galleries move their exhibitions online.

With the current coronavirus crisis, a lot of artists, galleries and other such institutions are rethinking curation, displays and the way exhibitions are held going forward and social media will become a critical part of everyone’s agenda.

What are you working on at the moment?

A new body of work called Umu Ada. The ideology of Umu Ada was created by tradition during the pre-colonial era where women were held sacred and they participated in collective decision making on political, legal and social issues. Long before the colonial masters arrived in Africa, during and after colonialism, women had been a vital cog within the Igbo society. Their involvement and representation in this process was primarily done through the Umu Ada .The Umu Ada are defined as the powerful daughters in Igbo culture. Umu Ada means native daughters of common male ancestors or “daughters of the soil’. Umu Ada is also collective term for all first daughters.

My proposed exhibition will highlight and acknowledge the various roles that the Umu Ada play in the political, economic, religious and social life of the societies within which they operate despite their limited access to resources and paternalistic domination.

I am very excited by this collection as it is challenging me on a number of levels. Needless to say – watch this space!

Follow REWA on Instagram at: artbyrewa

Website: www.artbyrewa.com